The History Of Art According To Jeff Koons

The art world’s king of pop talks us through the masterpieces that inspired his latest collaboration with Louis Vuitton

Photo: Mark Seliger

Jeff Koons

Art history has always been important to me. When I was starting out, I wasn’t familiar with the history of art and it wasn’t until after I arrived at art school that I learned how art was involved with the humanities. When I had my first art-history class, I realized I could have a dialogue with all these very moving areas of humanism— philosophy, psychology, aesthetics—and soon enough these areas became driving devices for me. I became very curious about what it meant to be human—what humanity’s true potential was, and how we might achieve a higher state of being through art. Art history became a way of exploring precisely that.

When I was younger I found it interesting that European artists of my generation would speak about art history in a negative manner and say things like, “As an American artist, you don’t have to carry the weight of art history on your shoulders, which gives you, Americans, the freedom to move around and make gestures that are open and powerful.” It has always been just the opposite for me. From the American perspective of Western European art, one could see that an artist like Manet was able to become Manet through an awareness of Titian, Velázquez, Watteau, and Goya, and this sense of connectivity was a really beautiful thing. It shows how one is able to find interest in something greater than the self.

“An artist like Manet was able to become Manet through an awareness of Titian, Velázquez, Watteau, and Goya, and this sense of connectivity was a really beautiful thing.”

If I look back at the works I’ve made over the last couple of decades, I think my relationship with art history makes itself very evident. I’ve always enjoyed creating works that would have this kind of gestalt presence, and many have been directly involved in the aesthetics of Dada, Surrealism, or, simply, classicism. In my “Banality” series, you can look at a work like Michael Jackson and Bubbles and see the same triangular-shaped configuration used in Renaissance sculptures, like Michelangelo’s Pietà. At other points, I also became very involved in the Baroque and the Rococo. During this period, everything felt like it was being negotiated, showing how certain styles are trying to meet the needs of people. What I love about that period, the Baroque, say, in Italy, or in South Germany, is that you can walk into a great Baroque church and not have a penny in your pocket, but you feel that there’s absolutely nothing to worry about as far as having food or shelter that day because the decor—the use of gold and silver leafing, and the abundance of nature (you can have plants, animals, and flying angels within the carvings in the architecture)—somehow makes you feel that all your immediate needs are met; worries seem to dissolve by themselves. You become subject to transcendence when you’re going through an experience of such visual strength and abundance: You no longer feel threatened by your immediate environment, which is precisely what I am striving to attain in my work.

Recently I went to a conference on Leonardo da Vinci, organized by Walter Isaacson at the Aspen Institute, and the speakers were some of the world’s top scholars on da Vinci, like Martin Kemp and Luke Syson. There was a lot of musing about what has made the Mona Lisa so iconic, but what I took away from this event was the importance of Leonardo’s relationship with nature and the individual. If you look closely at the Mona Lisa, you’ll realize how much the painting deals in fluid dynamics. From his experiments in physics and his observing autopsies, Leonardo became highly aware of fluid dynamics: understanding how blood flows through the body, in the same way that water flows through a stream. The neatness of such natural phenomena is very much at work within this painting, informing how all the movements in her hair interact with the background. This sense of oneness with nature is paramount to the Mona Lisa—another crucial feature that brings this work very close to my own concerns.

Related article: Louis Vuitton Announces A Second Collection With Jeff Koons

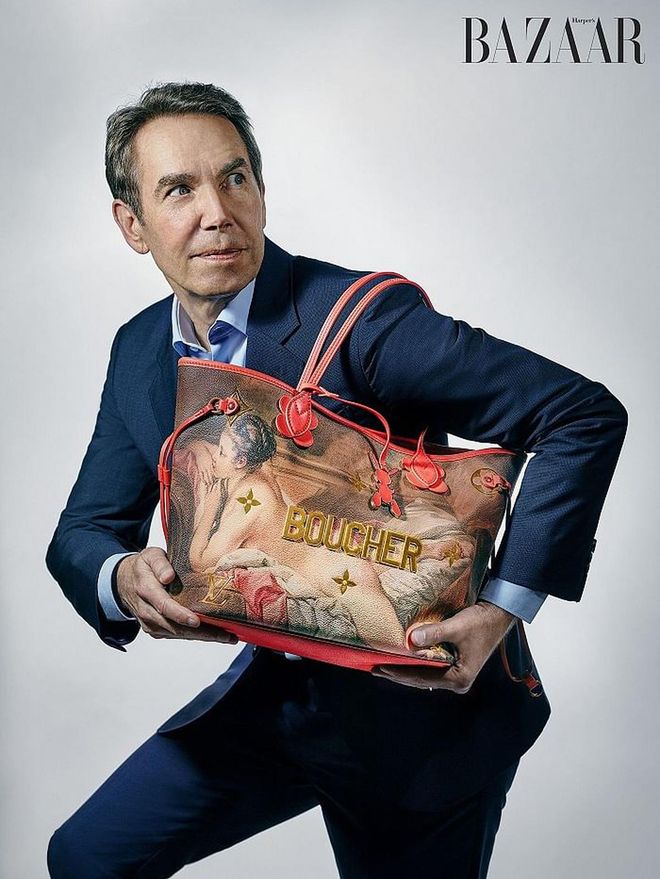

Koons with a Boucher bag from the Masters collection. Photo: Mark Seliger

Jeff Koons

I’ve always wanted to return to that sense of oneness with nature in my art, while also retaining the concept of artistic connectivity, which is essential to me. When you study art history, it becomes apparent that all the artists are making reference to each other—Rubens’s Tiger Hunt makes reference to da Vinci’s lost painting The Battle of Anghiari—and from a drawing by Rubens we have an idea of what The Battle of Anghiari might have looked like. It’s obvious that Rubens is picking up on all the dynamic qualities of da Vinci’s composition, and da Vinci, of course, was looking back to Verrocchio, Uccello, and Masaccio, so all of these works are invariably tied to one another. These ties are precisely what the “Gazing Ball” series aims to conjure up today. Likewise I would say the Louis Vuitton Masters collection further explores this fascinating correspondence.

Related article: First Look: See The Louis Vuitton X Jeff Koons Collaboration For Yourself

Looking at how I perform as an artist, I try to work with things from a very instinctive level, from a pure state, so for several decades I wanted to work with this object: a gazing ball. A gazing ball is a circular glass object that often has a reflective, mirrored surface. It comes from 13th-century Venetian times and was subsequently repopularized by the Germans under King Ludwig II of Bavaria during the Victorian era. I grew up in Pennsylvania, where there’s a large German population, and as a child I would see gazing balls in people’s yards, and this, to me, is a symbol of generosity. The gazing ball is so informative because it’s reflecting in almost 360 degrees, telling you where you are in the universe at that moment. But if you think of philosophy, of Platonism, for instance, the circular form is one of the purest—this spherical object is reflecting the world in its sheer simplicity.

When I was thinking about starting my “Gazing Ball” paintings, I wanted to pay homage to artists I truly loved by pairing them with this object that is both simple and omniscient. I have a highly intuitive process for making art, so I chose paintings that, very simply, I’ve always wanted to be surrounded by, like Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass or Olympia, both of which were very informative to me. All of the paintings I chose factor into the canon of Western art history, but the whole series can be thought of as my own artistic DNA. They are works that have always been vital to me. Pairing the images with a gazing ball was a way to heighten them by anchoring them in metaphysics and time. The gazing ball reflects the here and now, but it reflects you, the viewer, as well. So it affirms your presence while it also mirrors the painting, and in some way this allows you to time-travel and return to 19th-century Parisian life with Manet. At the same time, precisely because of Manet’s own humanism, you can feel a relationship to all the heroes and mentors who informed Manet—and informed me as well. I became inextricably linked within this rich, quasi-infinite humanistic cycle.

“Boucher’s Reclining Girl is a painting I often visit in the old Pinakothek in Munich. It strikes me as one of the most sensual images ever painted.”

Every work in Masters was first covered in the “Gazing Ball” series. But as my Masters collection is much smaller, I was really thinking about images that would create a balanced dialogue, so I would take one image that was more sensual, like Boucher’s Reclining Girl, but then, in the same series, you have Monet’s Water Lilies. The bags function in a similar way to my “Gazing Ball” series. On one hand, you may think it’s one of my artworks, so there is a certain symbolism present, like the interplay between the LV and JK initials and the presence of my Rabbit [each bag is adorned with a leather tag in the shape of a rabbit, a reference to Koons’s stainless steel sculpture from 1986]. On the other hand, all of this takes place within a very minimal format, to stress that this is not about me. It is not about my creation; it is an exercise in experiencing humanism, being in touch with your own humanity. It is about giving it all up to the artists featured on the bag, whether it’s van Gogh, Gauguin, Monet, or Turner. On the inside of each bag you’ll find a biography of the artist, and a short biography of mine printed on the leather. The interior presents a portrait of every artist in the series, while mine is just the Rabbit. So the whole experience is focused on the artist, the bag, and what it represents. I don’t believe that someone’s first thought upon seeing one of these handbags would be, “Oh, the owner of that bag loves to go to art museums.” I hope that what would come to mind is that this person is a proponent of humanism: They believe in the connectivity that makes us who we are, how our forebears have shaped the world that we live in, thus creating an opportunity to forge a better world for generations to come. This requires an active participation in respecting the past, while also being in the moment, and trying to define the future. Time is at play here. Think of the reflective, shiny Monogram elements, and the sensual quality of the materials: This keeps you in the here and now. Yet when you open the bag and find on the inside dates recounting the life and death of the artist and notice just how many cracks have developed in the painting [each image is reproduced from the original painting right down to the wear and tear], your own mortality comes into focus. Ultimately, to me, art history has to do with a dialogue, a kind of participating, and a love of relationships at the heart of cultural history.

Koons’s “Gazing Ball” paintings from 2015, which feature works by Boucher, Turner, Manet, Monet, and Gauguin

Jeff Koons

Related article: Louis Vuitton’s Collaboration With Jeff Koons Is Made For Art Lovers

From: Harper's BAZAAR US