How Singapore-Born Sandi Tan Went From Having Her Film Stolen To Winning Best Director At Sundance

Her must-watch documentary, Shirkers, is a movie mystery about the power of youth and the complexities of female friendships

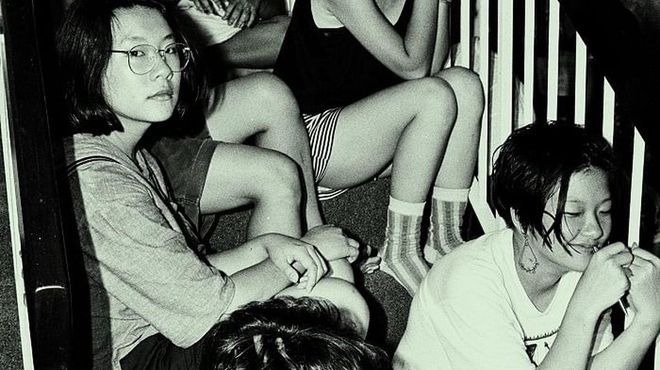

Photo: Courtesy of Netflix

Shirkers, Netflix

Imagine if you and your friends made your own film at age 18, shooting at a hundred different locations across Singapore, with hundreds of extras... Only to have the resulting footage stolen from you. That's exactly what happened to Sandi Tan, who along with her friends Jasmine Ng and Sophie Siddique, made a film, Shirkers, back in the 1990s—and wound up having their director, Georges Cardona, steal the final footage from them.

Photo: Courtesy of Netflix

Shirkers, Netflix

Now, 20 years later, the original film has become part of an extended documentary by Tan, thanks to Cardona's ex-wife returning the reels of film back to her upon his death a few years ago. Combining the original footage with interviews with the cast and crew, plus new montages, graphics and sound design, the resulting documentary is a fascinating whodunnit mystery about youth and friendships, in particular female friendships. Shirkers won Tan—who now lives in Pasadena, California—the award for Best Director in the World Cinema Documentary category at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, as well as caught the eye of Netflix, who bought the streaming rights to the show. We caught up with Tan, who was recently back in Singapore, ahead of Shirkers' premiere on October 26 on Netflix.

Photo: Courtesy of Netflix

Why did you decide to make Shirkers the documentary, and how did you decide you wanted it to take this form?

How could you not? First of all, it's an amazing story. Telling an amazing story can take many different forms, but to tell a film story, you have to have the footage. We had 700 minutes of 16mm film, which was transferred to digital in a lab in Burbank, California. I think it's the same lab that worked on a lot of Wes Anderson films, so they’re used to seeing amazing footage. But when they saw this footage, their jaws dropped. They just thought, "What? This happened in Singapore 20 years ago?" They couldn't believe it. They saw all the things we captured, like a hundred different locations, with a hundred different extras, and also the amazing dog, the largest dog in Singapore, Mega.

I realised watching this footage that these people had their possible futures taken away from them. How could I not want to tell their stories, and our story as well? To set about telling this, I had to find the correct form, which was not to do this as a straight documentary, but to do a more complex version; which would be the story of my coming to want to make films, and also encompassing all my friends, and my nemesis, Georges, as well. It took a lot of figuring out because it’s not your usual story; it’s very layered, very obsessed with recapturing where I was as an 18-year-old, and the frenzies in my head. We could not do an authentic film without capturing that at the beginning, which means I had to dive into my archives, and soak and marinate myself in all these letters, diaries and videos for a few weeks before I could really get into it. I listened to a lot of music and looked at a lot of pictures, and just experimented and played. To tell this crazy story, you had to find your own way, and like the original Shirkers, it was inventing my own way of doing things again.

Did it end up being a cathartic process for you and everyone else involved?

Yes. Making the film, solving the biggest jigsaw puzzle in my life... It’s very cathartic once you find the structure and you find the film, and you've told everyone’s stories in a way? I think the very act of film-making, and rediscovering my passion for film-making in the process, was the hugest reward. Also, for me to hopefully bring some kind of closure to all the other people who were involved in the project, who wondered what had happened to it, and how come [they] never got any news. For example, the woman who played the nurse, she flew herself to Sundance to surprise us. It was a meaningful episode in people’s lives, people who took time off to be part of this project, and I was really grateful to them. Not to give too many spoilers, but hopefully it was cathartic for the widow too, to see this kind of villainous (to her) character encased in the form of film. Maybe then it would be sort of exorcised from her life, contained; no longer haunting her and being malevolent to her in some ways.

The villainous character being Georges.

Right. I don't think of him as a villain, which is interesting, because a lot of people say, "Why don't you see him as a villain? How come you're not as angry?" But I'm not. I find him my nemesis, but that doesn't mean he is the villain. I think he is a very strange friend; he left me a lot of clues, and we keep playing cat and mouse, I feel like we are having this conversation even through the chasm of death. He both enabled my dream and thwarted it; it's both a gift and a curse that this whole thing happened, and we made this film, which is a much better film than the original Shirkers could have been. I do feel he is a nemesis in the [same] way as Sherlock and Moriarty or something, [him] giving me clues and I am still chasing; it’s still a conversation, it's still a game.

Photo: Courtesy of Netflix

Shirkers feels, at its heart, like a story about youth and friendships, in particular female friendships. Was that what you wanted to capture with the documentary?

Yes, very much so. I think almost every woman has friendships like that, which are very fraught, and you're almost like sisters, so you can fight for years and they know how to get under your skin. You can continue the conversation even if you haven't spoken in 10, 20 years. For example, when we showed at the Sundance premiere, me, Jasmine and Sophie hadn’t been in the same room together in 20 years, so that’s pretty amazing. But I think a lot of people can identify with that kind of friendship, and I wanted to show female friendships in that way because often you read about it in novels, you might see the fictionalised version on a TV series, but you never see it caught in real life, because this is how it really is.

I have to give credit to my DP (Director of Photography), Iris Ng. She’s a great Canadian-Chinese woman, very tiny with a big camera, very poker-faced. When she shot us, she vanished into the wall. So Jasmine was yelling at me, not self-conscious, because Iris was non-existent and the sound man just looked away. We managed to capture something I thought quite special, because most people are much more guarded.

What do you hope viewers will take away from the film?

I think it’s basically that you should always try and discover your secret superhero self. My secret superhero self, I discovered, was my 18-year-old self. I think that is true for a lot of people; you're a teenager, you’re not afraid, you’re not beaten down by life, and you just want to go out and do things with your friends or by yourself. I think everybody has that superhero self at some point in their lives, when you’re at your most creative, your most optimistic; and that secret superhero self should be rediscovered, celebrated and exalted. Don’t move ahead with fear; just keep going, persevere and be patient, because you never know when your setbacks may be overturned. It could be you yourself that overturns your own setbacks, and that’s the most liberating feeling in the world.

Photo: Courtesy of Netflix

Shirkers, Netflix, Sundance

You wrote for BigO magazine at age 14; made a zine, The Exploding Cat, at age 16; made a film at age 18, and was the film critic at The Straits Times at age 22. How did you end up being part of the independent arts scene and how have those experiences shaped you?

If you were growing up in Singapore in the '80s, nothing was going on. If you were a creative person, and you didn't find an outlet, make your own culture and make your own fun, you were gonna go insane. There wasn't the Internet where you could find your friends; I mean, my group of friends was so small and so insular. It was just the four of us: Me, Jasmine, [our friends] Ben and Julian; there was nobody else who had these kind of interests. I was always interested in films, but there was nobody giving film classes. In fact, Georges Cordona’s film class at The Substation was the first film-making class of that sort in Singapore. Jasmine and I did the Theatre Studies and Drama (TSD) programme at Victoria Junior College, so it was like a natural transition while waiting to go to school after our A-levels. That’s how we entered into that world. We were from that special milieu of TSD students—it was just a special group of very ambitious kids who were interested in the arts, but there was no outlet, no support system; once you got out of school, there was nothing, so you had to make your own world. I think that that was a great time to grow up. I hate to say it but now, everything is so easily available that you take everything for granted. You can shoot movies on your cell phone, but it’s not like you are more likely to do it because it's easier, because you take it for granted. Back then, it was so difficult that it became a special endeavour; almost like a mission that you and your friends do.

I do believe that making a film in the 21st century, with all this around you, you have to have a sense of fun. If you're going to recapture what it is like to make films back then, and what drew you to films in the first place, you have to have a sense of fun, and too many people don’t. The way I managed to do this was to work with a very inexperienced editor named Lucas Cellar, who is 27 and his background is in skateboarding. His only credits were non-credited runner on Spring Breakers by Harmony Korine and assistant editor on Author: The JT LeRoy Story, so he was very untried. We went at it backwards and [all these established editor friends] were horrified. They were so relieved when we finished the film, went to Sundance, and won the directing prize. Now, they’re all like, "How did you do that?" They keep watching the film over and over, trying to figure out these magic tricks, what I did. I’m like yeah, "Because you said i couldn't do it that way..." The logic of this story means you have to discover the story as you go along and have fun doing it. There’s no way we could have gone the traditional way because this was a story that only I could tell, and because I’m not a seasoned documentarian, I'm not bogged down by rules. I just went instinctively, and we did it in my garage, which is amazing.

Now that you've rediscovered your secret superhero self, can we rest assured that we will be seeing more things from you?

Yes. It’s the best thing in the world, to be able to make a film, why would you ever give that up?

And you never did.

Yes, I was a filmmaker even when I was writing a book, i approached it as a filmmaker. That’s what you do. You tell stories in whatever form you can that is available to you.

Related articles:

Wonder Woman II: Everything We Know So Far

Netflix Heartthrob Noah Centineo Responds To Internet's Thirsty Memes