These Singaporean Fashion Collectives Are Rewriting the Rules

Singapore fashion collectives Youths in Balaclava and Why Not? on community and creativity in a time of crisis.

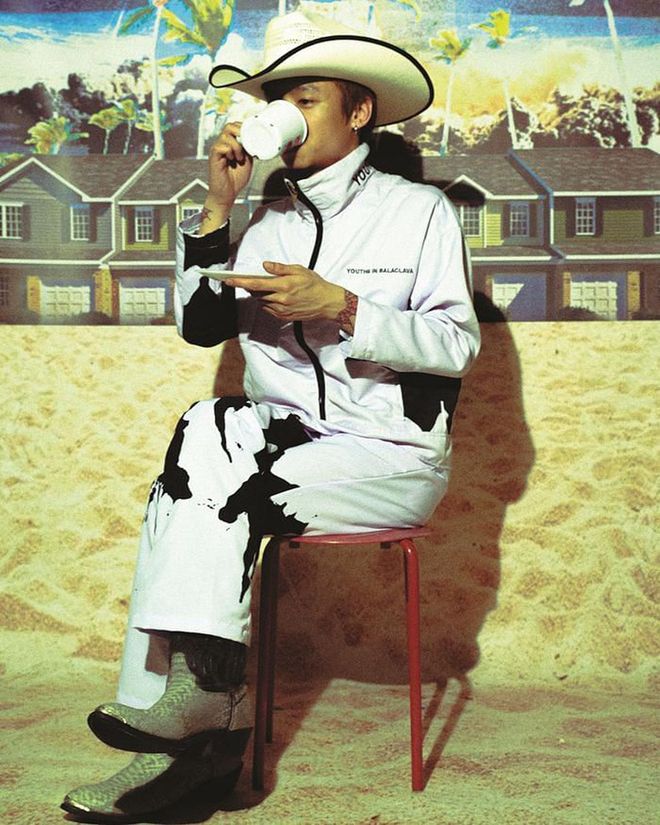

Youths in Balaclava spring/summer 2020Photo: Courtesy

YOUTHS IN BALACLAVA

This 13-member collective banded together in 2015 to create fashion that reflected their tastes and experiences. With a unique aesthetic that blended the languages of streetwear, Singaporean youth, film, music and various subcultures—so different from everything going on locally at that time—they quickly gained a reputation for being rebels and outsiders. It wasn’t too long though before mainstream recognition came knocking at their door. In 2017, they hit retail holy grail—Dover Street Market, and fashion insiders the world over quickly sat up and took notice. Last year, they upped the stakes with a Paris Fashion Week debut and now, Youths in Balaclava are stocked at the most cutting-edge global retailers, from SSENSE and Selfridges to 10 Corso Como and Galeries Lafayette.

Youths in BalaclavaPhoto: Courtesy

What led to the start of the collective?

The idea of bringing different people from different backgrounds together to exchange ideas and collaborate creatively. It’s a platform for these creative individuals to find an outlet for their voice without the need for any prior art background or a well-rounded resume.

What drew you to fashion?

Fashion was introduced to different members of the collective as different experiences, such as music and movies, and these made us pay attention to style. There was a strong attraction towards dressing well and knowing your references, and most of these references stemmed from things we observed around us such as media, music and art. The inspiration from these made us turn to the world of fashion as a form of expression.

And what do you want to express with your clothes?

We want to pay homage to the rejects of every era, as well as inject our personal life experiences into the styles we create but expressed with fabrics.

Related article: How Singapore's Fashion Community Is Giving Back During The Pandemic

Youths in Balaclava spring/summer 2020Photo: Courtesy

Who are the people that inspire you?

The radicals that were not afraid of the dark: Martin Scorsese, David Bowie, Tim Burton, Salvador Dali and Gravity Boys to name a few.

You went from being outsiders to being part of the system—how does that feel?

One advantage is simply being recognised for what we do and for it to be deemed as accomplishments; we were able to make a name for ourselves not just locally but on a global platform. People now understand that not only are we able to produce basic, everyday apparel but we also have the capability to produce a full collection with layers in our concept. The best part of the journey so far is to think of the times when we used to do this for fun but now call it our job.

How has the industry changed, if at all, from when you started?

We haven’t seen a major change, although we have noticed that more support is being granted to creatives with smaller followings. There is more attention being spread out to new creatives and the industry is giving them a platform. Compared to when we started, the local arts scene was not as supportive. I think what we’ve managed to do is to show local creatives that anything is possible with a little time.

Related article: The Graduating Class Of Singaporean Fashion Institutes Speaks Up

Youths in Balaclava spring/summer 2020Photo: Courtesy

What other changes would you like to see?

With the current pandemic, it is a reflective moment for the industry to make changes to its structure such as the number of collections a year and the resources used. Fashion is important in many different ways and it is a good time to think about how fashion can still play its part and remain relevant as the world recovers. The industry can look at changing how they do seasons, and brands would be less burdened to keep up and be encouraged to produce less.

What were your goals and plans for 2020 before the pandemic hit?

Our goal was to branch out onto more platforms and for the brand to grow bigger. Unfortunately, with the pandemic, Paris Fashion Week in June was cancelled. There was fear initially, since we only just started our journey. However, we’re remaining optimistic and taking this as another challenge to overcome. We look forward to improving ourselves and also the excitement to come as some of us approach the end of national service.

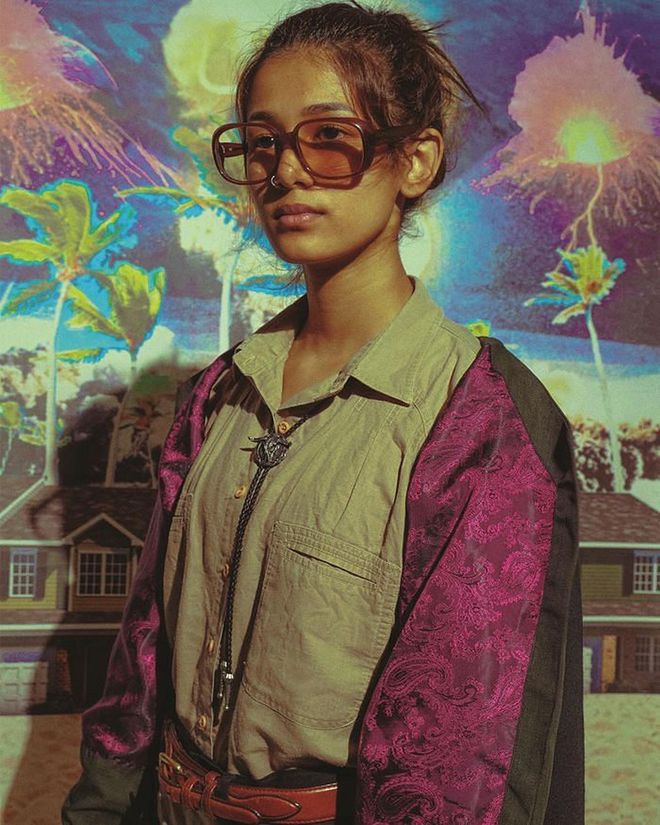

(L-R): Racy Lim, Manfred Lu, Izwan Abdullah and Miyuki Tsuji of Why Not?Photo: Courtesy

WHY NOT?

Frustrated by the restrictiveness and rigidity they see in the existing fashion school system here, fashion designer Manfred Lu teamed up with creative director Izwan Abdullah last year to put on their own showcase. They enlisted like-minded design students who shared the same sentiments to join them, as well as editor-curator-PR practitioner Racy Lim. The result was part guerrilla fashion show, part experimental performance art; but pure manifestation of youthful energy, with each designer conceptualising every last detail for their respective segments. In just a year, the collective has grown from nine to over 20 members, encompassing not just designers but creatives with backgrounds in writing, fine arts, theatre and graphic design.

How did the collective come about?

Manfred Lu: It started out with fatigue from the traditional art school frameworks in Singapore. We had enough of participating in a system of presentation that has not changed for decades—often a 30-second runway show no one watches. It turned into a questioning of our discipline, our goals and our careers. That’s when we came up with the question and the name: “Why Not?”

Izwan Abdullah: Designers spend half a year working on a collection to eventually have someone else decide how it’s going to be presented—it’s something that we need to start deciding ourselves. When something is not handed to us, we work for it and create it for ourselves.

What changes do you think the industry should make to better benefit the next generation?

Izwan: On the institution level, I believe that young designers deserve more autonomy. They are pressured to achieve a level of commerciality that is unattainable and a lot of artistry is lost in that process. Take away all the unnecessary embellishments; we don’t need more competitions. What we really need is a platform that allows for more collaboration resulting in relevant experience and exposure.

Racy Lim: Greater representation of non-binary identities, and modes of working achieved through non-capitalist frameworks. The people we involve need to feel truly respected and close-knit rather than merely ‘filling a gap’. Empathy and humanity are buzzwords often thrown around to make projects seem socially conscious but may not be reflected in the process. That in itself is also a form of exploitation.

Related article: GINLEE Studio Embraces Slow Fashion With Its Latest Order-On-Demand Initiative

A look by Manfred Lu at the Why Not? 2019 showPhoto: Courtesy

Is there a common thread that unites the work of the different designers in the collective?

Manfred: It’s interesting because our collective is made up mostly of designers and writers who never received formal education in fashion. It’s a great balance of different points of view, and I think our collective critical questioning of the fashion system was what brought us all together.

Miyuki Tsuji (Project Manager ): We thrive on each other’s creativity and energy. Every designer’s starting point and inspirations are completely different so the outcome and mood should be completely different. However, because we work very closely as a team, this could somehow unintentionally form that common thread of similarity, but it’s never too apparent nor in any way emphasised.

What were your goals and plans for 2020 before the pandemic, and how are you navigating it?

Izwan: As with last year, we were working towards our annual guerrilla show. The designers and the rest of the collective had been working tirelessly on fundraiser parties and the show content. The pandemic has challenged us further to think about the form and structure of our show.

Manfred: Without spoiling too much of our plans, I think we’re looking at a bigger picture now. With the digitalisation of fashion shows and growing signs that the system would indeed slow down after the crisis, I think there’s an opportunity for a dialogue and a change in our message.

A look by Putri Adif at the Why Not? 2019 showPhoto: Courtesy

What drives your work?

Racy: Class and community divisions have existed for a long time, but recent events have made them a lot more difficult to ignore as our behaviours are concentrated more than ever in the digital space. This has led us to think about how we—as individuals and a collective—can motivate more tangible actions to help bridge these societal and structural gaps.

What are your hopes for the collective?

Izwan: Our biggest goal is to raise fashion to the same stature as art. What we want is to change the Singaporean perception of fashion and for young creatives to be more daring and empowered to do what they want to do.

Manfred: It’s not easy, but it has to become the norm for designers to aspire for autonomy in all aspects of their work.

Racy: First and foremost, the project cannot exist to soothe egos. An initiative that is aimed at motivating progress and change cannot function in a self-serving manner—we’re extremely mindful that the process and outcome must remain genuine. In the long run, we want to be a space that people trust enough to turn to because they know there’s no social alienation or people doing things just because “it’s cool”.

What are your thoughts on commerciality? At this stage of your career, is it a concern?

Miyuki: As I am only at the beginning of my career, commerciality is something I try not to think too much about. But growing up, it’s something that inevitably gets ingrained in me. I do often work around the idea of creating works that I think could sell but so often I realise it becomes somewhat like a safety cushion, which makes me lazy, and then I end up revoking and redoing the work.

Manfred: Not at all. We’re still a very young collective, and it would be a mistake to be blinded by the temptation of commercial success. After all, we’re not doing this for the money.

Related article: TAFF Continues To Support Innovative Brands With The Third Edition Of Its TBFI Programme